`

Excerpt from

Emotion as Motivated Behavior

George Ainslie

Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Coatesville and Temple Medical School

116A VA Medical Center, Coatesville, PA 19320

Published in Canamero, Lola, Ed., Agents that Want and Like: Motivational and Emotional Roots of Cognition and Action (Proceedings of a Symposium at the Artificial Intelligence and Simulation of Behavior 2005 Convention, Hatfield, UK). AISB pp. 1-8.

![]()

Hyperbolic discounting greatly simplifies the problem of modeling the emotions. With conventional, exponential curves, a person should be able to estimate what emotions will be most rewarding for what durations, and plan accordingly. To correct this picture to match the real world, a modeler has to impose negative emotions on the subject, and limit her access to positive emotions, by a combination of hardwired and conditioned reflexes. By contrast, hyperbolic discounting lets emotions be behaviors that compete in the common market of motivation. In such a model, emotions differ from deliberate but volatile behaviors like paying attention only in producing significant intrinsic reward. The patterns of this reward determine both emotions’ quasi-involuntary property and the motive to limit their occurrence—the negative emotions by an admixture of obligatory nonreward that overbalances their reward at all but very short distances, the positive emotions by the premature satiation that will occur unless the subject limits what occasions their occurrence.

5.1 The Demon at the Calliope

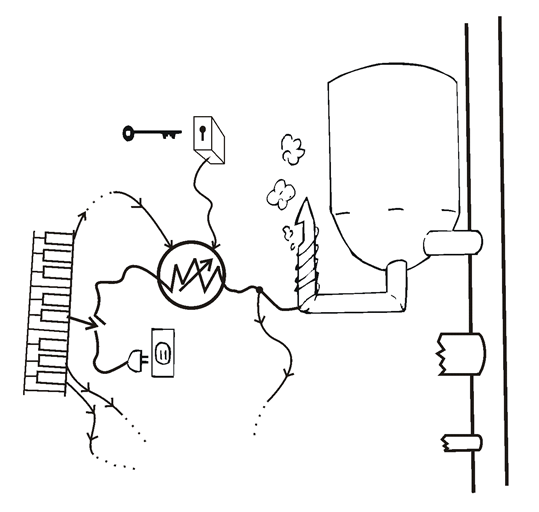

This situation can be portrayed by an automated model, and even a mechanical one. I will describe the latter for better illustration (cf. Ainslie, 1992, pp. 274-291). The individual is divided into a motivating part and a behaving part. The motivating part is the brain function that generates reward, modeled by the whistles of a steam organ (circus calliope). The calliope has individual steam boilers heated by their own circuits—one for each separately satiable modality of emotion, such as anger, sexual arousal, laughter, and even grief and panic (figure). Other boilers exist for nonemotional options such as muscle movements. The behaving part is a demon who presses the calliope keys according to a strict instruction: “Choose the option that promises the greatest aggregate of loudness x duration, discounted hyperbolically to the present moment.”

A single boiler heated by current that is controlled by one key of the calliope. The whistle can blow as long as it has heat and water; the water is replaced in the boiler at a rate determined by the diameter of the intake pipe. A rheostat governed by hardwired factors including turnkey stimuli and current flow in other boilers can modify current flow, and current flow can affect rheostats on other boilers. The loudness of the whistle is not a linear function of the amount of steam produced; it is disproportionately less at very low and very high values.

5.1.1 Properties of the calliope

Pressing a key sends electric current through heating coils around its boiler, causing release of steam through the whistle at a delay and over a time course determined by several factors:

- The shape of the boiler. Narrow necks limit loudness, and bigger tanks hold more water, modeling the potential intensity and duration of the emotion.

- The density of wiring around the boiler neck relative to its diameter. This models the speed of arousal.

- The amount of water in the boiler. This models physiological readiness for the emotion (something like “drive”).

- The rate at which the demon presses the key. Pressing too slowly wastes the effort, too fast exceeds the whistle’s sound-producing capacity and wastes steam.

- The diameter of intake pipe to the boiler, modeling the rate at which readiness regenerates

- The presence of turnkeys to the rheostat (variable resistor) in the heating wire, modeling the extent to which hardwired stimuli (e.g. pain) facilitate the emotion. Emotions vary in their readiness to occur without hardwired turnkey (“unconditioned”) stimuli, and a given process varies among individuals, as in the traits of fear- or fantasy-proneness. This readiness is modeled by what is the lowest setting of the rheostat.

- Activity in the heating coils of other boilers that are hardwired to raise or lower this rheostat. For instance, pain might augment sexual arousal or decrease laughter.

5.1.2 The behavior of the model

The demon has whatever estimating ability the whole individual has, which I do not model further. Emotions are all wired for fast partial payoffs, although their long run payoffs are variable. Because of their fast payoffs they have a great ability to compete with other choices on the demon’s keyboard. Because hyperbolic discounting makes curves from imminent payoffs disproportionately high, the demon will often be lured into negative emotions—those that do not have enduring payoffs and that lower the rheostat on other boilers—when a turnkey stimulus is present and/or readiness is high. For the same reason he will press wastefully and not get the most steam from the available water in positive emotions if he presses keys ad lib. Thus he will be motivated to tie his pressing to the appearance of adequately rare external cues.

5.2 The value of the model

A quantitatively accurate model would reflect the time course of neuronal processes, of course, most of which are still unknown. Even the sites of interaction of the components that I have illustrated are merely the simplest that will relate the dynamic of hyperbolic discounting to the known properties of drive and emotion. I do not pretend to fit the promising but still sketchy single neuron physiology and fMRI data that are beginning to emerge.

The point of this crude model is to add flesh to the bare mathematical fact that hyperbolic valuation curves describe the temporary dominance of some SS outcomes over some LL ones. That property makes possible a model that uses only one selective process (reward) instead of the conventional two (classical conditioning and reward), and that requires all learnable processes, even emotions, to compete in the single internal marketplace of motivation. A one-process model is not only more parsimonious than the conventional one, but also better fits the phenomenon of mixed emotions—the strangely addictive quality shown often by anger and sometimes even by grief and fear. Beyond that, as I have argued elsewhere (2001, pp. 175-186), a model of emotions that has stimuli serve as occasions for them rather than rather than control them makes possible dynamic theories of the psychological/social construction of facts and of empathy as a primary (not instrumental) good.